Maintaining potato varieties in tissue culture – and why variety trials are important

Apologies for the late post – I have been struggling with image alignment in my posts. Sorry if things are a little askew!

Today we have a guest post by Amy Charkowski, who leads the lab I work in. She is the director of the Wisconsin Seed Potato Certification Program. You may not know that all commercial seed potatoes start off as small plantlets grown in a nutrient medium – we refer to them as tissue culture plants. Read on for an explanation of why we use tissue culture to maintain potato varieties, what can go wrong, and why field trials are important to maintaining varieties.

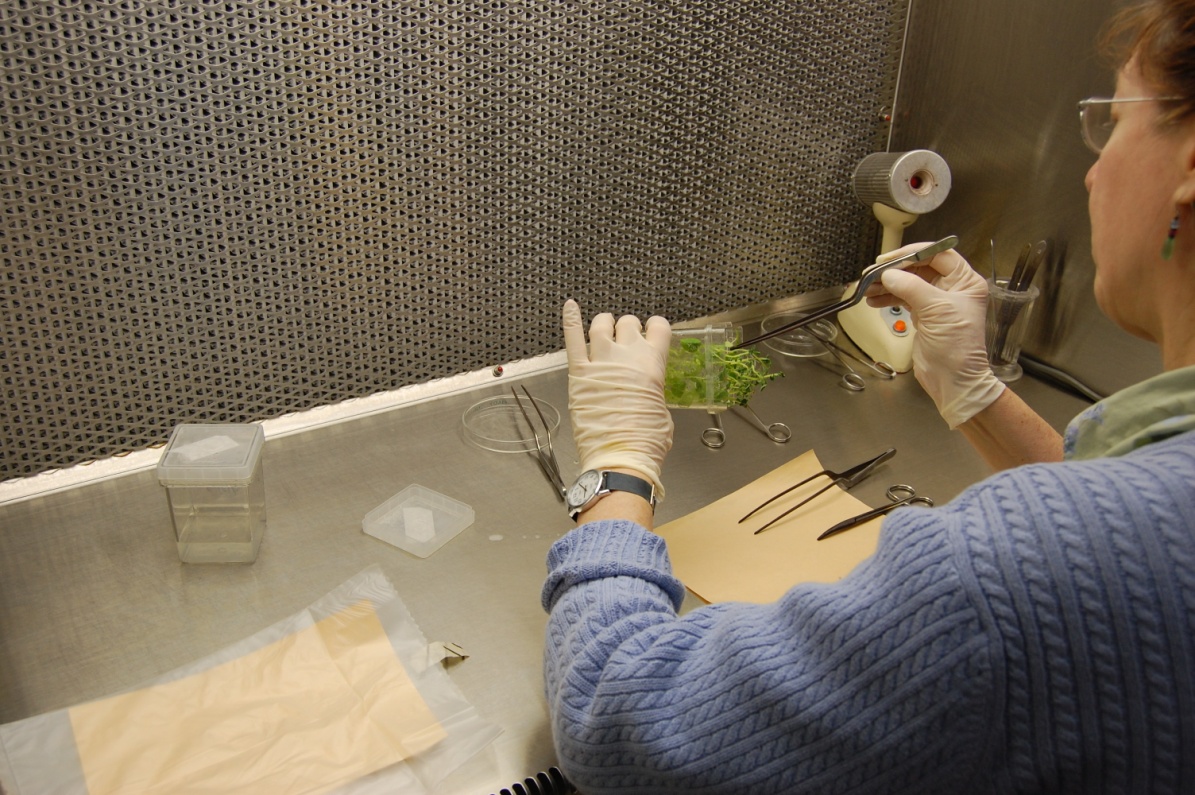

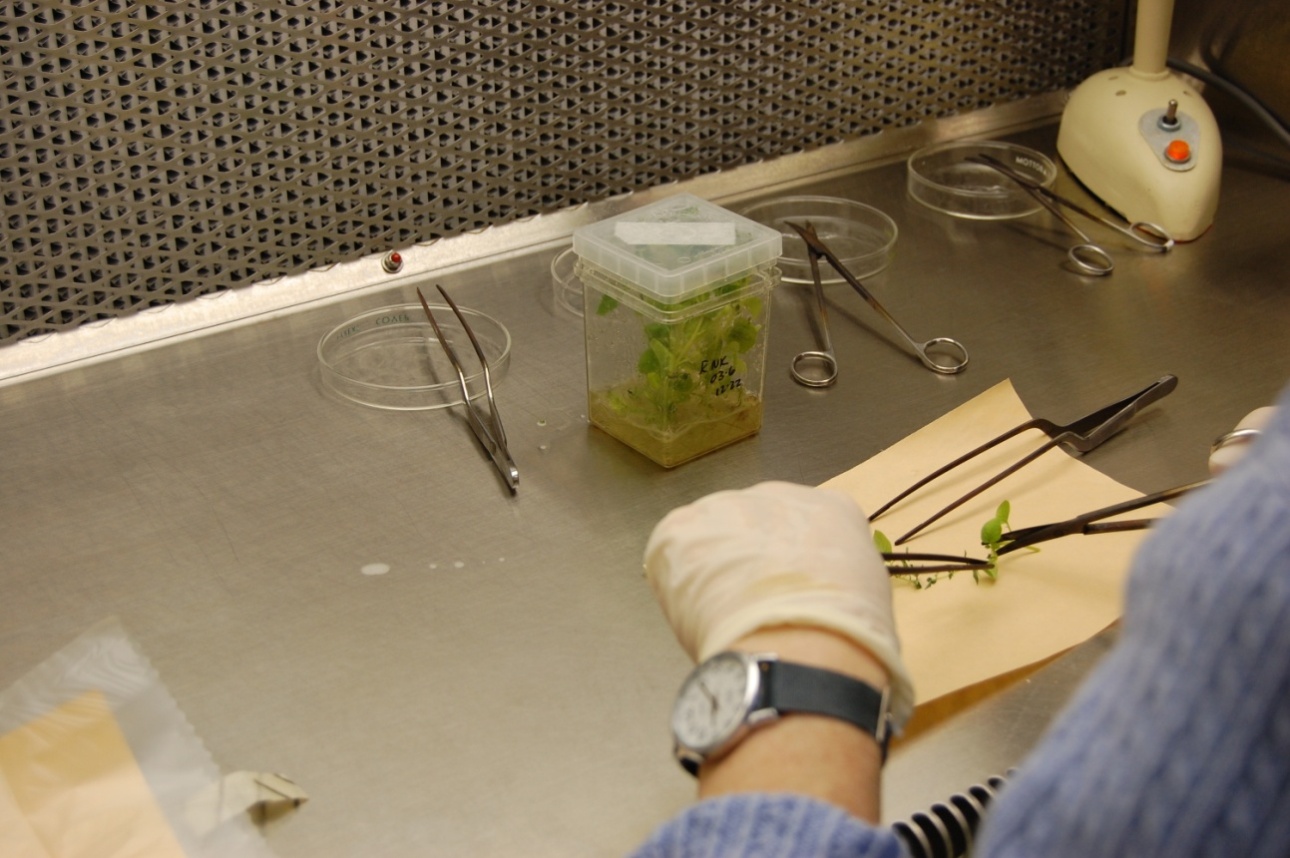

Tissue culture plantlets. Most potato varieties are maintained in test tubes, baby food jars, or plastic cubes with tissue culture methods. These plantlets are grown on an agar gel – an algal extract – combined with a nutrient solution containing the essentials for plant growth.

Micropropagation methods are used to produce tissue culture plantlets. Essentially, a plantlet can be cut into pieces, each of which contains a node with a leaf, and the nodal cutting is placed into a new container. We can usually get 3 to 4 cuttings per plant and within 3 to 4 weeks, each nodal cutting will grow into a new plantlet. We can use this method to produce thousands of pest and disease-free plantlets per year in a small amount of space.

Potato plantlets can also be stored in test tubes for long periods of time as either plantlets or microtubers. Plantlets can be stored for up to 9 months before they need to be transferred to new gel and microtubers can be stored for up to 5 years.

What can go wrong with tissue culture? Unfortunately, there are many things that can go wrong when people produce plantlets in tissue culture. Bacteria and fungi also grow on the nutrient gel used to grow the plantlets, so we need to work with these plantlets only in laminar flow hoods. A laminar flow hood is a box with a fan that blows air through a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate absorption) filter that removes all bacteria and fungi from the air.

We also need to protect the plantlets from small insects that can quickly spread throughout a collection of plantlets. For example, thrips and mites multiple quickly on tissue culture plantlets and these pests can bring in and spread plant viruses. Therefore, once someone has gone into a greenhouse or field, they do not work with tissue culture plantlets again that day since they may carry pests on their clothes after visiting greenhouse or field plants.

Even if the plantlets remain free of pests and microbes, they may mutate. Each time any type of cell replicates, including potato cells, there is a chance that a mutation can occur. Most mutations do not have large effects, but sometimes these mutations have significant effects on potato physiology. Mutations can occur in the field as well as in tissue culture, and sometimes these mutations lead to new varieties. For example, the variety Dark Red Norland is simply a version of Red Norland that has a naturally-occurring mutation that caused the tubers to be a darker red.

However, sometimes mutations cause loss of yield, vigor, or shape. It is impossible to tell if this has happened by looking at a tissue culture plantlet. Since we and others usually only maintain a few plantlets of each variety, if a mutation happens, the original variety can easily be lost. Unfortunately, the only way to assess the plantlets is to grow tubers from these plantlets in the field.

The Lelah Starks Elite Foundation Seed Potato Farm assesses potato tubers grown from standard varieties, such as Red Norland, Superior, and Yukon Gold, every few years to confirm that the tissue culture plantlets have not mutated. We have seen several examples of mutations, such as Dark Red Norland tubers that have lost their dark red color, Lamoka that have changed flower color, and Silverton Russet that have switch from indeterminant to determinant growth and that have lower yield.

Unfortunately, with the Seed Savers Exchange heirloom collection, we don’t know if mutations have occurred! The descriptions for most of the varieties are limited, so we don’t know what they looked like when they were entered into the collection. Also, like us, most places that maintain potato lines in tissue culture lack the resources to check their entire collection each year.

By helping us grow out these varieties on your farms, you are helping us develop descriptions of these heirlooms and also helping prioritize this collection so that we and others can try to maintain the most interesting or useful lines without detrimental mutations.

This article was posted in Blog Posts, Uncategorized and tagged tissue culture.